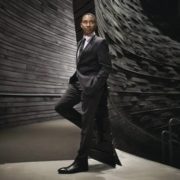

Jay Ellis And Stephanie Nur Illuminate Love Without Borders In ‘Duke And Roya’

/0 Comments/in Duke & Roya, For Theatre, Love In Afghanistan, News /by divatamer

In Duke and Roya, a young American rapper and an Afghan interpreter meet in Kabul under the most unlikely of circumstances—on a U.S. military base where he is performing for the troops. What unfolds is a cross-cultural story that defies expectations and borders, both literal and emotional.

“It’s a love story,” says Stephanie Nur, who plays Roya. “It’s cleverly written and unexpected. You’ve never seen this combo onstage or on screen before. These are the kinds of stories we need—told from different perspectives and rooted in real human experience.” Nur, whose credits include 1883, Special Ops: Lioness, and My Big Fat Greek Wedding 3, makes her New York stage debut.

Written by Charles Randolph-Wright and directed by Warren Adams, the play, which is currently running at the Lucille Lortel Theater, has evolved over more than a decade. Randolph-Wright began writingDuke and Roya while a resident artist at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. A prolific writer, director, and producer across film, television, and theater, he was inspired by a book about women in Afghanistan that “floored” him.

“I thought, we as Americans are so myopic. We have no idea about the rest of the world and are taught to stay in our own little box,” he says. So he wanted to share a story about human connection that transcends those boundaries.

Ellis was drawn to the play’s honesty and vulnerability. “It was the human experience,” says Ellis. “To watch two people from completely different worlds explore each other and themselves—it’s magical. They’re just having a conversation, saying, ‘We’re different, but that doesn’t mean we have to scream at each other. That doesn’t mean we can’t find understanding. Their relationship is flirty, sexy, romantic, and beautiful.”

Ellis performs original rap songs onstage—his first time rapping professionally. Songwriter and artist Ronvé O’Daniel collaborated with Randolph-Wright to create the raps that mirror the layered identities of the characters.

From the creative team to the cast, the process of making Duke and Roya has been deeply collaborative. “It’s a very open room,” says Dariush Kashani, who plays Roya’s father. “We are with people who really care and are open to each other’s ideas.”

The team—including producers Kerry Washington and John Legend—was drawn to how the play centers the transformative power of love in a divided world. “These are the kinds of stories we need,” says Noma Dumezweni, who plays Duke’s mother. “They are told from different perspectives and ask the big question: How do we connect?”

For Randolph-Wright, Duke and Roya couldn’t be more timely. “People’s rights are being taken away,” he says. “Even if you are not exactly like the characters in this play, you will identify on some level. I love collisions—and this play has a lot of them. But the problem now is, we’re not allowed to have collisions. We’re not allowed to educate, or to have joy. And joy is imperative in the midst of devastation.”

Duke and Roya explores intimacy, identity, and the universal need to feel loved. “Without knowing anything about the play, anybody can buy a ticket, sit down and be moved,” says director Warren Adams.

Producer Naturi Naughton-Lewis encourages audiences to “come with an open heart and mind—ready to take the ride and go on the journey with us,” she says. “I hope we make hearts flutter,” adds Nur. “I hope people leave talking about what the play means. And I hope it brings more empathy into the world.”

Dariush Kashani and Noma Dumezweni

Dariush Kashani and Noma Dumezweni