In Broadway’s ‘Trouble in Mind,’ the Past and Present of Theater Collide

The narrative has been two-fold since Broadway returned in September, following an unprecedented 18-month shutdown: Broadway is back, but it’s also better.

These sentiments were underscored most visibly by something that had never happened before the 2021 season. The works of eight Black playwrights — alongside a community of predominantly Black directors, casts and crews — were going to be mounted across the nation’s largest theater district.

But tucked within the momentous celebration was an important question: Why hadn’t this happened yet?

While this type of question is frequently asked of the ceiling breakers, director Charles Randolph-Wright points to those who hold the answers — white counterparts and industry leaders who have historically had the power to remove the ceiling altogether for Black playwrights like Trouble in Mind’s Alice Childress.

“Ask them,” the director, writer and actor says. “Because we all did the work. We trained, we jumped through hoops. We did all the things you were supposed to do, and all too often, it did not happen.”

This experience of exclusion is among the many threads that link Randolph-Wright and Childress, two South Carolina-born artists and the creatives behind Roundabout Theater Company’s Broadway production of Trouble in Mind, which runs through Jan. 9 at the American Airlines Theatre.

When she was alive, Childress’ work never made the leap from Off-Broadway, where it debuted more than six decades ago. But the director, who first read the play while in college, says he shared her dream of telling this uncompromising story to a Broadway audience.

Ultimately, it would be not just the dream but Randolph-Wright’s unyielding tenacity — equal to that of the late playwright — that carried him through his 15-year quest to cement her in the Broadway canon and lexicon.

“Someone said that this was a lost classic,” Randolph-Wright recalls. “It wasn’t lost. Lost is when it’s in a drawer and someone doesn’t find it. It’s been there and regional theaters have performed it for years, but it’s never before gotten the acknowledgment of what a Broadway stamp does, what that pedigree does.”

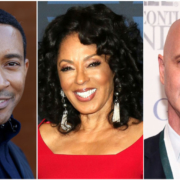

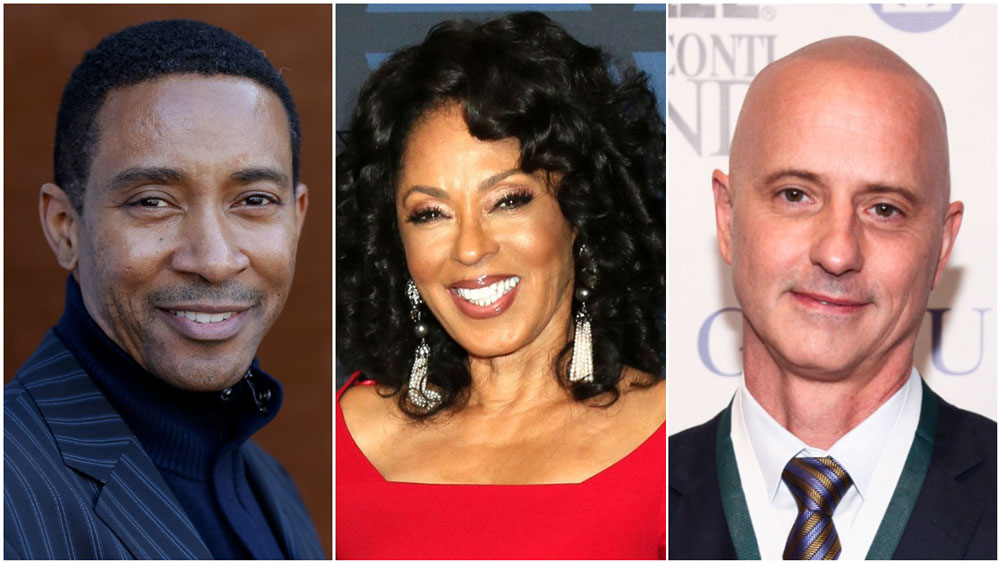

Based on Childress’ own experiences with the theater, the show follows Black actress Wiletta Mayer (played by LaChanze) as she navigates the production of the anti-lynching play Chaos in Belleville alongside a mixed Black and white ensemble led by a white director. (In real life, Trouble in Mind‘s cast includes Jessica Frances Dukes, Don Stephenson, Simon Jones, Chuck Cooper, Michael Zegen, Alex Mickiewicz, Danielle Campbell and Brandon Micheal Hall alongside LaChanze — a company Randolph-Wright says “truly had the love for each other to be honest” and “brought the best to Alice’s words.”)

On stage, this show-within-a-show is pitched by its fictional white director as some newfangled look at racism in America, guaranteed to open the eyes and hearts of white audiences. But the disparaging treatment of Trouble in Mind’s fictional actors and the offensive representations they’ve been tasked with performing are a series of cuts for LaChanze’s Wiletta that eventually turn into a gaping wound.

No longer willing to settle personally or professionally, the actress demands the show’s Black company members be acknowledged in the creative process, risking her career and the entire show as she calls out the hypocrisy and racism of its white leadership.

“I directed it completely over the top because it is so wrong in how it is performed. The director in the play keeps saying to the actors, ‘I want you to be honest, I want the truth,’” Randolph-Wright says while recalling how he explained his directing approach to one of the actors. “I said, ‘You have to understand. That is his honesty, and that is his truth for Black characters to be so ridiculously stereotypical.’”

That sentiment is particularly striking after learning why Trouble in Mind hasn’t graced a Broadway stage before this fall. After opening on Off-Broadway in 1955, it was expected to debut in 1957. But white male producers asked the playwright, novelist and actress to tone down her story’s commentary about race.

Like her leading woman, Childress refused to censor herself — an act of bravery, notes Randolph-Wright — and so the dream of bringing her story, which deftly tackles racism, sexism, class and privilege in American theater, to Broadway’s stages was deferred. In this way, Trouble in Mind is a mirror for an industry the director says has given certain people “the entitlement and the privilege of saying, ‘I know better than you about who you are.’”

“They refused to put that on stage then, but people still have problems seeing that right now,” Randolph-Wright says. “I think it’s difficult because the people who control a lot of the work, I don’t think they want to put themselves up there on stage that way. So, bravo that Roundabout has placed this world on stage because it’s very accusatory of the whole system and speaks to how we change this system.”

It is all very meta, with no word changed in Childress’ script for its contemporary audience and nuanced helming from a director who says he has never had equity with his white peers. Randolph-Wright is also the first Black director LaChanze has had “in her 35-year career on Broadway in a leading role.”

“An actor was asking a question about the play being over the top, so I had every actor of color that day tell one story about a white director who told them how they should be Black,” Randolph-Wright says. “The youngest Black actor in this company, who has starred on a couple of television series and is in his 20s, even had this happen to him in the past few years.”

Trouble in Mind and this Broadway season, then, is not just a mirror. It’s a moment to splinter the past from the present for artists working at a time when, like the fictional play’s lead, “people have felt, ‘I am not doing this anymore. Some things will have to change.’”

“Who is designing the set of the house, who was putting them in the clothes, who is marketing the show? You may do this Black project, but you walk in the room and everyone who’s presenting this project — none of them look like you,” the director says of what inclusion has historically meant on Broadway. “So what has changed this season is that many people have received opportunities that they never received before.”

In Trouble in Mind, 12 performers and crew made their Broadway debut, including Black female lighting designer Kathy Perkins. She’s “worked all over the world,” including on Childress’ last show, Randolph-Wright says, but “never got her shot on Broadway before this year.” She’s now among less than a handful of Black lighting designers in the history of Broadway.

That shared experience across decades as Black artists “so used to not being seen and heard,” the director says, is why Childress’ work is so fortuitously fitting for Broadway’s current moment of self-reflection. While talks about the play’s Broadway debut with Roundabout had started years before the summer of 2020, it arrives amid a historic but deeply challenging time that could see artists’ work treated as both a pandemic test run and an indistinguishable creative mass.

“I didn’t want this play to be a knee-jerk reaction to last summer, for this to come out in the middle of all of this, on the front lines. I didn’t like the idea of, ‘Here we are again, a monolith,’” he says. “We were the canary thrown in. It was obvious to so many of us that this was the time but my fear was that if these plays failed, then they would say, ‘Well see? We tried.’”

And yet, the director concedes that Childress’ work may have debuted exactly when it needed to. Broadway seems finally ready to commit itself to the kind of creative authenticity and accountability Wiletta demands, thanks in no small part to this season’s swell of Black artists.

It’s a moment the director likens to the years following the 1918 influenza, which birthed the roaring ’20s and the Harlem Renaissance — a stark parallel that makes him wonder what theater’s renaissance will be after this pandemic. “Is this the beginning of that?” he asks.

If it is, it’s perhaps best illustrated not just by what’s happening on stage or behind the curtain but in front of it. Childress’ debut is among a collection of plays encouraging a shift in who makes up a “Broadway audience,” with Randolph-Wright calling responses to the play from Black students especially “breathtaking.” White viewers, he says, are changed, too.

“In 2019, the typical Broadway white audience would not have heard this play the same way they are hearing it now,” the director says. “Alice is getting her due at a time when people are realizing things they would not even think about before — that wasn’t even in their periphery.”

The photo was shot on stage at the American Airlines Theatre (227 West 42nd Street) where the show will begin previews on Friday, October 29 ahead of an opening set for Thursday, November 18, 2021. This is a limited engagement through Sunday, January 9, 2022.

The photo was shot on stage at the American Airlines Theatre (227 West 42nd Street) where the show will begin previews on Friday, October 29 ahead of an opening set for Thursday, November 18, 2021. This is a limited engagement through Sunday, January 9, 2022.